What To Expect When You're Expecting.... New DGAs..

Uncertainty about the future of Dietary Guidelines

Last year, I wrote a history of nutritional guidance in America, covering how nutrient reference values, dietary guidelines and food guides have evolved across our country’s history and the factors that shaped that evolution - everything from an increased understanding of the science of nutrition to war and politics. In writing that piece, I never could have predicted the factors shaping this upcoming edition of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGAs). As of writing this, it has been publicly stated by the HHS Secretary that massive changes to the DGAs are incoming, with the new guidelines being just 4-6 pages (our current 2020 DGAs are 160 pages). I’ve talked with several reporters anticipating the new DGA release (initially supposed to come before August, but now delayed) and figured I’d put some thoughts down on what we might expect and the implications of the coming changes.

For the uninitiated to the nutrition world, we get new DGAs every 5 years - the guidelines are mandated by an act of Congress (1990 National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Act) that calls for the secretaries of the USDA and the HHS to jointly publish them.

The DGAs are informed by an advisory panel, the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC). The DGAC is formed in compliance with the Federal Advisory Committee Act and its purpose is to review the science published since the previous edition. The guidelines have varied over time in their approach but in recent history, have employed 3 major methods to establish recommendations.

The DGAC does analyses on the most recent data related to nutrition - think national data on current food/nutrient intakes and relevant nutrition metrics (e.g. body weight, nutrition-related disease prevalence). This helps define the scope of nutrition-related problems as well as current dietary patterns/nutrient intakes and where shifts are needed to meet the guidance.

Systematic reviews of the literature are undertaken on key questions that are laid out beforehand by the Departments. These help summarize the data related to these questions, which often cover topics related to pressing issues and nutrition-chronic disease links (as an example, one of this most recent cycle’s questions related to the relationship of Ultra-Processed foods to obesity).

Food pattern modeling is done to assess whether recommended dietary patterns (using foods found in the American diet) reach estimated nutrient requirements. This might sound a bit boring but this modeling is often what defines quantitative limits for intakes of nutrients of public health concern like added sugars.

These approaches collectively aims to ensure recommended dietary patterns result in the consumption of adequate levels of essential nutrients to maintain physiological function and reduce the risk of chronic disease. Once the DGAC scientific report is complete, it is ultimately passed off to the Secretaries and departmental staff across the federal government to be turned into the DGAs. The DGAs are then intended to be used by various federal sectors (e.g. National School Lunch Program, Military, Women Infants Children, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, federal labeling efforts, etc) as well as health professionals.

This process has been relatively normal for the upcoming 10th edition of the DGAs - right up until the change in administration. The DGAC report was released in Dec 2024 and USDA/HHS should have been in the normal process to write the DGAs and release before the year’s end. A few key public pieces of information have now informed us the DGAs will be dramatically different:

In an April interview during an elementary school visit in Virginia, RFK Jr stated that the DGAC report ‘looked like it was written by the food processing industry’. He has gone on to since tell Congress that "We're going to have four-page dietary guidelines that tell people essentially, eat whole food, eat the food that's good for you" and has since reiterated this in news reports - our HHS Secretary in this linked clip claims that his administration inherited the DGAs from the Biden administration that was poisoned by the same industry that put Fruit loops on top of the Food Pyramid, seeming to both misunderstand that he inherited the DGAC from Biden, not the DGAs and that foods at the top of the now very sunset’d food pyramids were actually the ones intended to be minimized.

Makary, the head of FDA (typically less involved with DGA development), has also made comments about the DGAs. He indicated that the ‘FoodPyramid is out’ (again, not been used in decades) and that they’re going to both engage the top nutrition scientists (what the DGAC already does..) and use ‘common sense’ to make the new DGAs.

We also got some information about specific changes related to saturated fat to come in this DGAs. HHS, USDA and FDA folks held a press conference with the International Dairy Foods Association where, alongside announcing the voluntary removal of artificial food dyes from ice cream and the approval of a 4th new natural food dye (gardenia blue), Makary commented on the new dietary guidelines, indicating a rollback on saturated fat recommendations and a nod towards Ancel Keys revisionist history. It is an interesting choice to announce rollbacks on long standing dietary recommendations on saturated fat with the industry that produces foods that are the major sources of them (dairy fat is mostly saturated) - it is even more interesting in light of how much this administration has claimed to be taking a strong stance on getting conflicts of interest out of the guidelines and reducing industry influence. If you’ve been following this administration, who they associate with and who has been quite activated in this era - Vani Hari (FoodBabe), Mark Hyman, Eric Berg, Gary Brecka, Nina Teicholz, the Means siblings, etc - some of these changes won’t be too surprising.

Despite only a little having been said, there are some pretty substantial implications for the future of federal nutrition guidance and policy. Some commentary:

A sticking point for the HHS Secretary seems to be that the guidelines are long and overly complex - thus, we just need a simple 4 pager to tell people how to eat. There’s a few points to unpack here:

In indicting the length, Kennedy regularly seems to confuse the DGAC report (>400pgs), and the actual DGAs (see a recent example screenshot below). This is not a small thing to mix up - the DGAC report is a scientific advisory report, the DGAs are a policy document informed, in part, by the DGAC report. The DGAC are experts who are volunteering their time to summarize the state of the literature (in collaboration with a ton of career staff) so that the government can have evidence-based policy. This report being 400+ pages is a feature, not a bug - you want a massive, transparent document based on a clear process to inform the DGAs, so that you can justify nutrition policy to the public as well as have some rebuttal to the various interests (everybody from from corporations to state-level officials and activist groups) who inevitably critique the DGAs and policies coming from it.

A reasonable reader might say, sure Kennedy confuses the DGAC with the DGAs but DGAs are still >100 pages and don’t feel accessible to the public. This is fair but also misses the mark on what the DGAs really are: a professional and policy document. You can see this directly stated in the guidelines.

2020-2025 DGA Executive Summary clearly indicating the intended audience of the document are not the public. The end-user is supposed to be a trained professional and/or policymaker who can benefit from that 164 pages that describes the state of USA nutrition, the process to establish the guidelines, the elements of various dietary patterns, foods/nutrients of concern, special considerations across life-stages, etc. Nutrition is highly specific to the individual and community served by clinicians and policymakers and its unlikely that a short 4pg document is going to contain an adequate level of detail and be flexible enough to be useful across the many nutrition situations faced by professionals across the United States (think everything from counseling lactating moms at WIC through to planning diets that are adequate for those in middle age at risk of chronic disease and the elderly in long-term care homes).

The fact that the DGAC and DGA are relatively inaccessible to public audiences does not mean that the public is not considered - there are a bunch of nutrition education materials that come from HHS and USDA that are much more consumer friendly. The act of developing food guides (e.g. the Food Pyramid being the most historically notable but MyPlate being the most recent edition) is a major effort of the USDA to communicate the DGAs to the public in a digestible manner, leaving the complexity for the longer DGAs. If you’ve not explored MyPlate’s website, it’s got infographics, healthy eating tips, an App, a meal planner and more (including in multiple languages). One can certainly question how effective the federal government has been at advertising MyPlate and related health messaging but the government has certainly not just dumped a 164-page complex document on the public and run. It is a real shame that RFK Jr and Co seem more interested in building anti-establishment energy by pretending the DGAs are long and out of touch, and mocking the long phased out Food Pyramid, rather than genuinely trying to increase resources to overhaul the content and increase the reach of public-facing healthy eating information coming from the government.

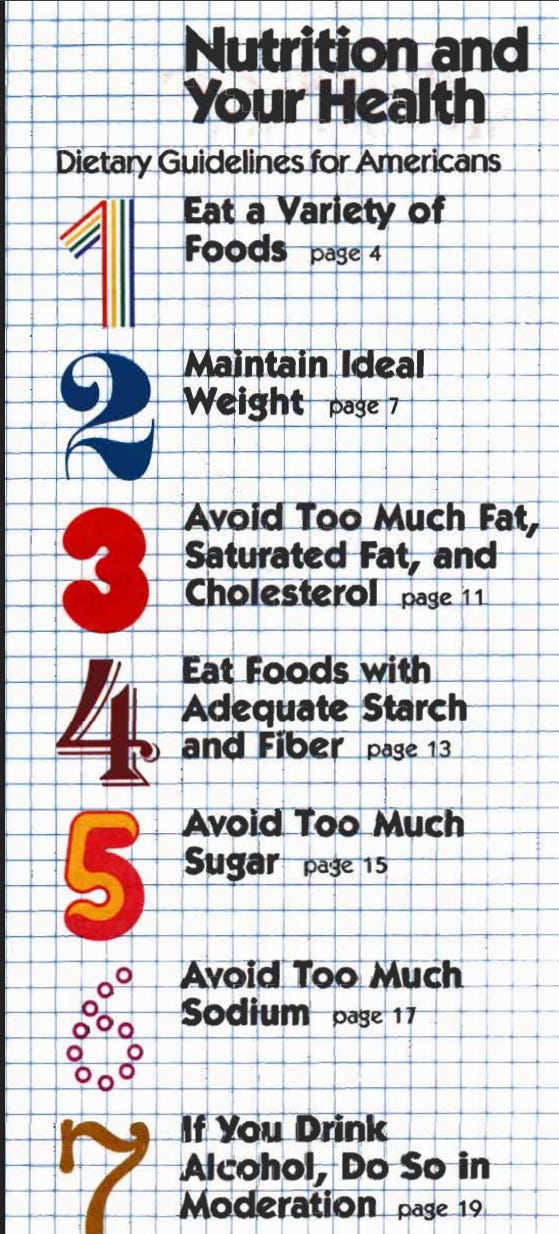

The whole notion of having a short 4 page dietary guidelines rests on the idea that Americans just lack the knowledge about what to eat to be healthy, and that if we correct that knowledge deficit, folks will change their eating behaviors and health will ensue. To be clear, I’m all for dumping money into a campaign to publicize generally accepted nutrition advice - we’ve been recommending folks to eat fruits and vegetables and fiber and less sugar since day 1 of Dietary Guidelines with limited success. Unfortunately, the knowledge deficit approach alone to public health is a failing one. The idea that simply providing general nutrition advice via dietary guidelines will enact widespread dietary change and combat nutrition-related chronic disease just has no basis in reality. Many changes to the guidelines over the years have occurred in the way we’ve messaged (emphasizing swapping over eating more/less, dietary patterns over single nutrients) with no real change in intakes. Major public health nutrition wins have come through passive changes like folic acid fortification or federal action and reformulation, such as with trans fats’ GRAS status being removed and industry replacement by high oleic oils. Apart from these system-level interventions, the best evidence we have for changing dietary intakes and moving the needle on nutrition-related chronic disease risk factors like excess adiposity comes from intensive lifestyle interventions that use multi-component interventions including education, 1:1 counseling from a dietitian as well as group sessions, gym/equipment access and time with a trainer, self-monitoring tools, and more - even then, when we look at these interventions, effects are modest and don’t always persist, so it’s a bit of a pipe dream to think that a generalized, non-individualized advice from a guideline is going to make significant impacts. If they were, the short pamphlets style of the original dietary guidelines should’ve caused widespread change but there’s no evidence they did, with even basic clear advice around avoiding sugar failing to stem the tide of high sugar sweetened beverage intakes in the ensuing decades. Changing diets is a taller order than simple provision of nutrition advice, a lesson that underlies why we’ve evolved towards DGAs being more meaty policy documents.

So what can we expect from the changes that we’ve been told are coming? In short, chaos. Predicting the effect of going from a 160 page document that drives numerous policies across the federal government to a 4-6 page document is challenging but there’s almost no way that 4-6 pages can recapitulate the 160 when it comes to federal programs. Consider a couple tangible examples: