During the 1960s-1970s, the topic of nutrition in the United States captured the nation’s attention. Ancel Keys’ cover of Time magazine launched the issue of nutrition, obesity and chronic disease risk into public awareness. Simultaneously, potentially high rates of undernutrition alarmed the public, spurred by ‘hunger tours’ undertaken by Senators Kennedy and Clark in 1967, Congressional hearings, and a CBS documentary titled “Hunger in America” as well as some national data.

Public concern spurred political action. President Nixon held the White House Conference on Food Nutrition and Health to examine policies needed to improve nutrition in the USA. Congress directed DHEW (now HHS) to launch a large Ten State Nutrition Survey (1968-1970) to assess the degree of the undernutrition problem -a survey that began the quantitative interrogation of the still-relevant links between poverty, race and nutritional status in the USA.

Congress also established the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs to “study the food, medical and other related basic needs among the people of the United States” and to “establish a coordinated program which will assure every US resident adequate food, medical assistance and other related basic necessities of life and health.” The Committee is largely the force that molded the political and social capital that existed for nutrition at the time into action. It worked for nearly a decade on numerous initiatives, research agendas and policy in coordination with experts, professional organizations, farmers, advocates and industry, and left a long legacy that we still recognize to this day: the expansion of the national school lunch program and food stamps, the creation of the Women Infants Children (WIC) program and a role in establishing a couple of the USDA Human Nutrition Research Centers are some of the most notable. The Comittee also addressed the emerging links between nutrition/obesity and chronic disease with its publication of the 1977 Dietary Goals, the precursor to the first edition of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans published in 1980. You can read more about this history in an excellent review here.

I have found myself thinking back on this history often over the past 6 months as we have seen this new administration and the ‘Make America Healthy Again’ movement rise to prominence. The “MAHA” era is arguably the first time that nutrition has captured the national consciousness since this 1967-1980s era and for good reason - rates of obesity and diet-related chronic disease are staggering and every metric of diet quality shows that Americans generally get failing scores. For a fleeting moment, I held a small bit of hope that maybe MAHA would do some good for nutrition - that it might have its own Senate Select Committee-type wins to point to- and that the floodgates of harm (ie rollbacks on vaccines) would hopefully be held back. 6 months in, I think it’s clear that that intentional naivety is no longer useful.

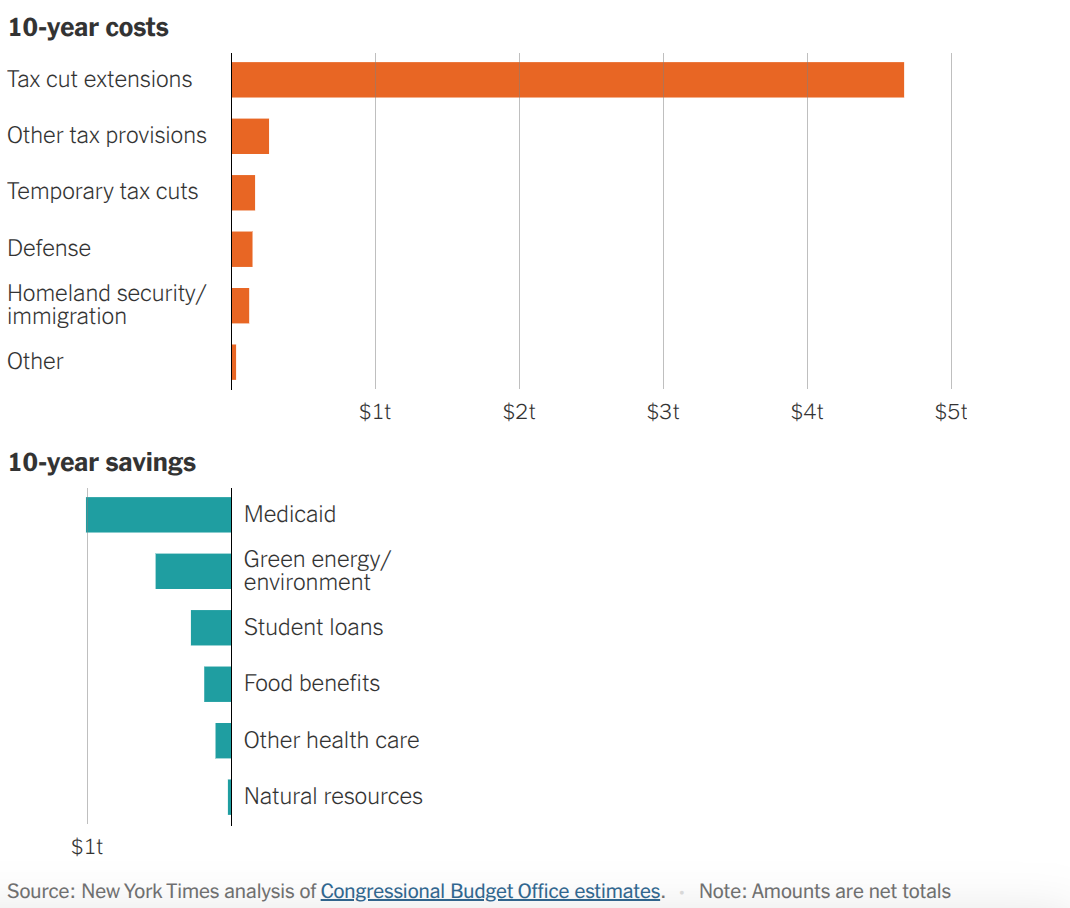

I write this as the ‘Big Beautiful Bill’ has passed both the House and Senate to arrive at the President’s desk for his signature. The Bill contains significant cuts to SNAP and Medicaid (something that impacts not only healthcare but automatic enrollment in free lunch for kids), trading our social safety net for food/nutrition over the next decade to offset tax cuts for the wealthy.

These cuts are yet another dissonant slight to add to the list for folks who hoped MAHA would do some good - here’s a non-exhaustive list from the past 6 months:

Cutting $1 billion from USDA for local food purchases for school lunch and food bank

A proposed 40% cut to the NIH budget for the 2026 fiscal year, unlikely to facilitate a much needed reinvigoration in nutrition research funding

Huge cuts in FY26 to SNAP and WIC, including rolling back fruit and vegetable benefits for mothers and their children (quite the opposite of tackling diet quality and chronic disease risk in children).

Efforts to censor a top intramural nutrition scientist at the NIH doing some of the only work manipulating processed food in the diet and studying how it might influence obesity risk - Dr Hall ultimately left the NIH, hamstringing efforts to link diet to chronic disease risk and information that could inform industry formulations.

Landmark nutrition trials, like the Diabetes Prevention Program, have had their funding cut. We’ve seen the defunding of major nutrition departments, like Harvard’s, and several molecular & community nutrition grants at Cornell get cut for no justifiable reason.

USAID, a major funder of global nutrition work, has been eliminated.

There’s been at least short-term disruptions in responding to lead crises due to cuts at the CDC. The FY26 budget has caused concern amongst advocacy groups aimed at reducing lead exposure.

the efforts of DOGE have caused substantial cuts at the FDA and CDC that are hard to estimate still. It is clear that FDA has long suffered from a limited budget on food issues and the human foods program (HFP) needed a boost, not cuts (the indiscriminate firing at HFP led to the director quitting and an unclear state of things there as the government has attempted to bring folks back and hire new employees). Food safety lab funding and staff was cut but supposedly reinstated. At a time when the administration’s priorities were around more rigor in food additive assessment and heavy metal monitoring - something that would require a massive infusion of funding - we’ve only seen cuts and chaos, not investment.

Easy to lose sight of admist the chaos and coming tangible harms to public health nutrition is the opportunity cost. Unlike the Senate Select Committee of the 1970s, there’s been limited engagement between the admin/MAHA and broad stakeholders to define the challenges facing nutrition - everything from funding of nutrition research to monitoring of the nutritional status of the population, to the very real need to look at the food value chain and consider every policy lever that can be pressed to shift diets more towards current dietary recommendations. Doing this would be hard work - getting Congress to appropriate funds for a massive, much needed investment in nutrition research; expanding coverage/reimbursement for individuals who want to see nutrition clinicians like registered dietitains (currently these are minimally covered by insurance) — and further expanding funding for intensive lifestyle interventions programs; considering industry taxes like the UK’s sugar levy; implementing mandatory limits on portion sizes and nutrients of concern in foods (eg. sodium, sugar); limiting advertising on food categories linked to negative health outcomes, particularly to children; expanding food labeling initiatives; re-examining food subsidies; strengthening standards in the school lunch program and investing in incentive programs in SNAP/WIC; investing in ‘healthy’ food processing methods. The list goes on and on of the serious ways we could invest in nutrition and metabolic health at-large.

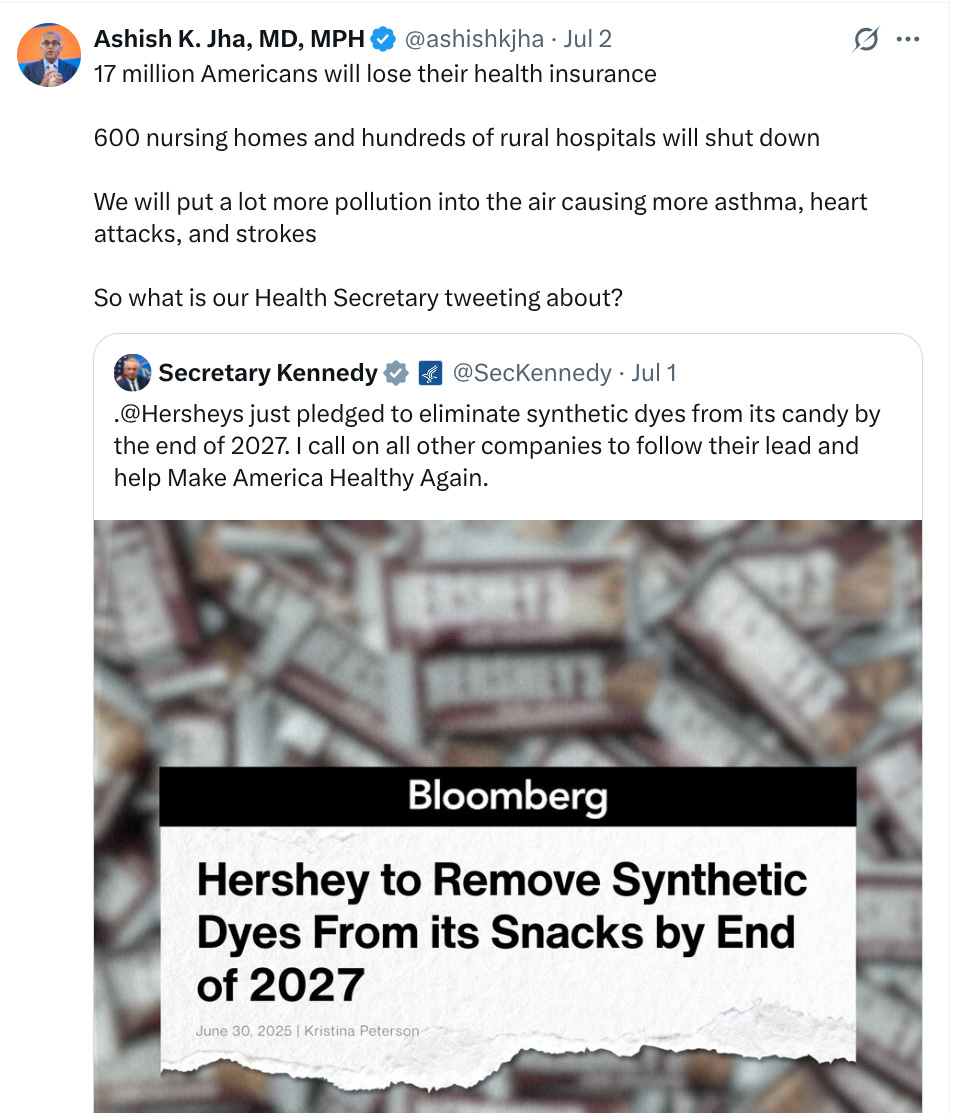

Unfortunately, most of what we’ve gotten from the administration and MAHA is either un-serious or low impact. There’s been a lot of oxygen-sucking performance, like photo shoots taking raw milk shots, commentary on the long-sunset FoodPyramid and absurd commentary on seed oils in infant formula. Most of what we’ve seen is 2014-era Food Babe messaging (you may remember the yoga mat chemicals petition against the food chain, Subway) about artificial dyes and replacing them with natural dyes. I’ve written a bit about artificial dyes before and am not going to rehash that all here but in short, the harms of the dyes and thus public health wins of removing them are pretty questionable — and they’re most commonly found in foods that we’d recommend minimizing consumption of regardless of the presence of natural or artificial dyes. The swap to natural dyes also isn’t without it’s own health risks, as members of the pediatric food allergy community have been highlighting. Even if you’re a fan of the focus on artificial dyes, the administration hasn’t taken many tangible steps - there’s been limited federal action apart from approving some news dyes, and no changes to the food additive regulatory framework that allowed them to be approved in the first place (the current framework wouldn’t capture risky ‘natural’ dyes’ impact on neurodevelopmental outcomes either). Rather than tangible action, the administration is relying on “agreements” with industry to reformulate away from artificial dyes (industry has denied such agreements), largely trying to take credit for efforts already underway by the food industry, who have been planning to phase out dyes due to state-level legislation that has created a patchwork of what dyes are approved to be sold in specific states (industry regularly opines that state to state and country to country differences in regulation require complicated manufacturing/formulation pipelines that complicate their business). It’s overall an odd approach from the administration to say on one hand, that companies are producing dyes that are poisoning kids, and then turn around and strike an ‘agreement’ with said evil companies rather than using the powers of the FDA to remove artificial food colouring certifications (maybe that is coming but I suspect given that the FDA had recently reviewed the limited data on food colours and childhood behavioural outcomes and not come to the conclusion of clear harm that the new administration is capitalizing on existing industry efforts over regulations where the science isn’t totally in their camp). Kennedy has continued to emphasize that the administration is working with food companies and getting them to remove ingredients without the need for ‘regulation’ (regulation isn’t needed since FDA already has the authorization to revoke approvals for additives and colours found to be unsafe). The partnering with industries you think are poisoning kids is bizarre on its face, but it feels even more daft to see our HHS secretary celebrate candy makers committing to reducing synthetic dyes on the same day Congress is voting on cutting Medicaid and SNAP, things that are ostensibly very not-MAHA.

At 6 months in, I think it’s time for food and nutrition advocates, scientists and professionals to call out the MAHA agenda for what it is - it’s a movement with the right vibes, the wrong priorities and solutions, headed up by someone with dangerous thoughts on public health who is not going to improve the health of Americans, nutritional or otherwise. We’ve seen professional societies in medicine get much more vocal, particularly as its related to vaccines and Medicaid cuts but unfortunately, we’ve seen limited leadership or pushback from nutrition societies like American Society for Nutrition or the Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics (the latter has had a few action alerts of late, as SNAP funding - an employer of RDs particularly for SNAP-Ed- has risked being cut). I’m not sure what these societies (or most leading tenured experts in the field who’ve also sat inconspicuously quiet) are waiting for - there’s so much opportunity here to provide guidance and professional pushback on what’s happening. I understood the desire to be quiet early on given the potential for harm but given all we’ve seen happen and what is proposed- NIH cuts, FDA cuts, NASEM cuts, CDC cuts, SNAP cuts, WIC cuts - I’m not really sure what anyone is still holding out for? The opportunity to update the Infant Formula Act that will functionally look the same as the codex standards industry already follows? That’s the only bottom of the barrel ‘win’ I can scratch from this admin so far.

Not only do we face existential cuts to research funding and huge threats to public health nutrition, we see zero energy and commitment for taking the MAHA energy and making it truly be something transformational. We look back on the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition after 50 years and can point to so many landmark nutrition happenings. When we look back on MAHA in 50 years, do we really want to point back to removing artificial dyes from still-sugary snack foods and rolling back nutrition for the most economically disadvantaged in society? It is time for the nutrition community to emerge from the sidelines and show genuine leadership without kowtowing to the administration: coordinate policy agendas, produce expert guidance on scientifically contentious issues, identify key areas of uncertainty that the government needs to invest in systematic data reviews and novel research, engage with the actual public who make-up the MAHA movement, be vocal when its own community members’ research gets cut unjustifiably and most importantly, align with broader medical and public health societies to ensure improved nutrition doesn’t come at the expense of science-based public health policy. Nutrition has been under-invested in at every level for decades and its time to get strategic about seizing the energy of this moment to turn it into something good - without losing our integrity or credibility by aligning with folks who are fundamentally anti-expertise and anti-public health. Whatever baseline hopes folks in nutrition had that enabled the mental gymnastics to become bedfellows with the admin, it should be abundantly clear by now that bootlicking behind the scenes isn’t going to make nutrition great again. There’s no nutrition win coming, let alone one worth the undermining of public health that we see happening.

Addendum:

For any who might be wondering why folks in the nutrition community might have been blinded by opportunity and sought to work with MAHA, there's a historical desperation that gives reason for some empathy. From any vantage point that you view nutrition, people have felt starved/neglected for a while.

Passionate about federal change in policy? The story of Michelle Obama and her substantial efforts to improve the food system that were heavily pilloried are quite sobering.

Want to improve dietary guidelines? The 2015 saga turned into a disaster re-evaluating the entire process and questions about the science (the drama prompted millions to be spent reviewing the science on sodium to functionally change nothing about recommendations).

Advocate for nutrition and prevention for the everyday person or patient populations? Coverage for Registered Dietitian services are still extremely limited to the point that most don’t get reimbursement for their services, restricting access to those who can afford it or those with already advanced disease.

Interested in nutrition research? The funding for nutrition science is pretty bleak, particularly if you care about human nutrition intervention studies - the infrastructure for undertaking this work was largely gutted in the 2000s and we’re going on over a decade of having limited rigorous new evidence emerging.

The investment in pregnancy and child health research is limited, national nutrition monitoring and surveillance is limited, investment in food composition databases is limited - I could go on and on but you get the picture: many nutrition folks across the spectrum have sat hoping that MAHA would bring the field much needed attention, funding, regulation and sweeping cultural change. I think it’s beyond the point where this hope is defensible but these all play into the feeling of collective exasperation and willful blinders many in the field put on to the red flags that were there from the beginning.